Cloud Services

Cloud computing has become a significant and rapidly growing part of the global computing infrastructure. It enables organisations to access a wide range of computing resources over the internet, including processing power, storage, networking, and software services. Instead of building and maintaining their own data centres, businesses can leverage cloud services provided by companies, with the largest cloud providers being Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP), although other cloud providers are also available.

In simple terms, the “cloud” refers to vast networks of remote servers and data centres managed by these providers. Rather than hosting applications and storing data on local servers and computers, organisations can rent computing resources from cloud providers as needed, on a pay-as-you-go basis. This offers advantages such as scalability, flexibility, cost-effectiveness, reliability, and robust security measures.

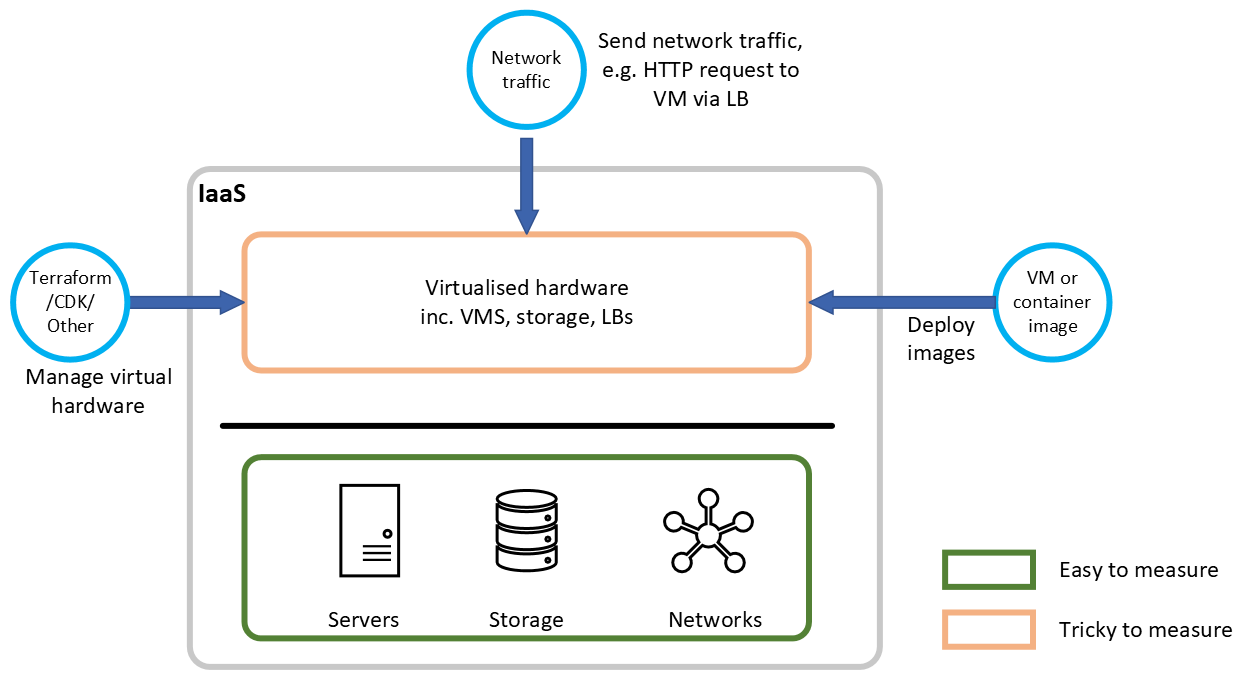

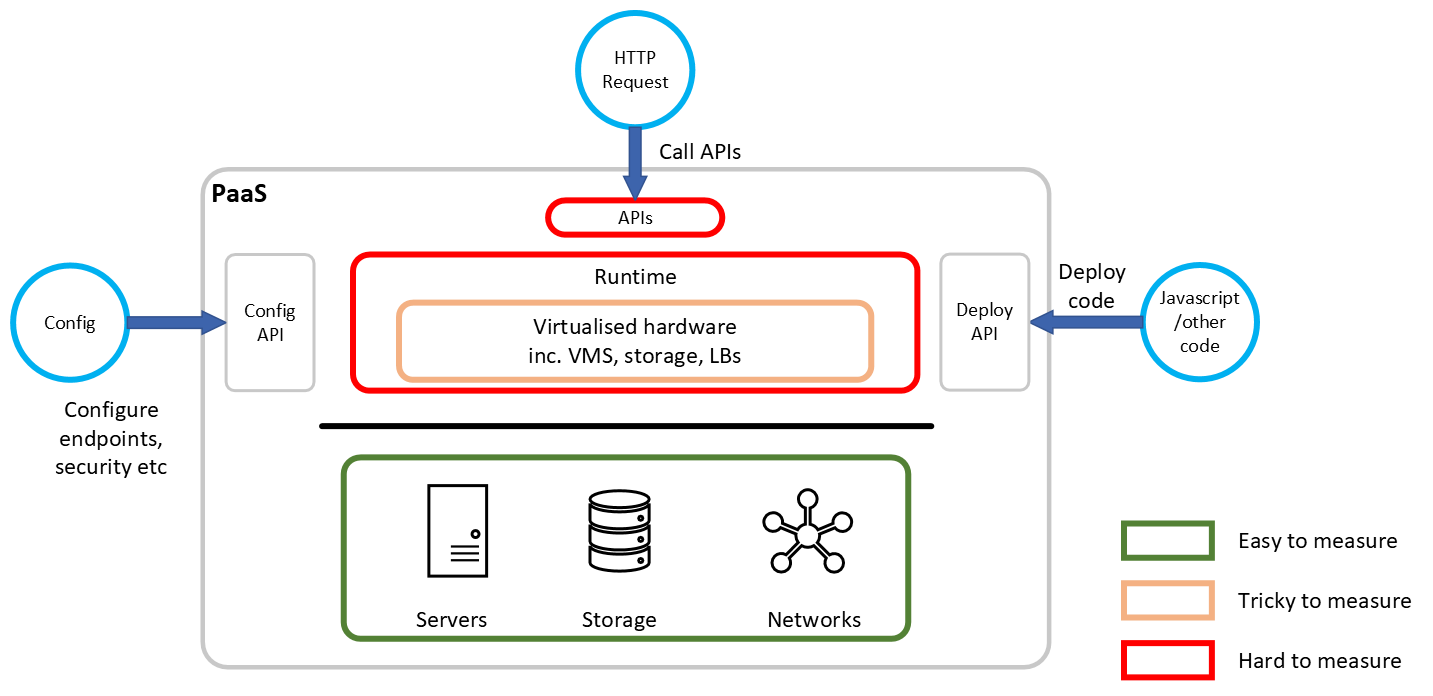

Cloud services are typically categorised into different models, such as Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) and Platform as a Service (PaaS) as illustrated below.

IaaS provides access to virtualised computing resources like servers, storage, and networking, allowing organisations to manage these resources as needed.

PaaS removes the need to manage the underlying infrastructure like hardware and operating systems, which can streamline development. This can extend to services like managed databases, where the cloud provider takes on the responsibility for administration and maintenance.

The diagram above summarises this and indicates the relative challenges of measuring carbon for real hardware vs virtualised hardware vs the PaaS case where only an API is visible and there’s no access to the underlying virtual or physical machines.

Environmental Impact of Cloud Services

The environmental impact and carbon emissions associated with cloud computing are becoming increasingly important considerations. The energy consumption and carbon footprint of cloud data centres have grown substantially as the adoption of these services has accelerated. This hardware has its own upstream and operational emissions, which are attributable to clients under Scope 3 of the GHG protocol. Despite improvements in energy efficiency, the sheer scale of cloud infrastructure means its collective emissions are significant.

At the same time, cloud computing presents some opportunities for improved sustainability compared to traditional on-premises data centres. Cloud providers can leverage economies of scale to invest in more energy-efficient hardware, cooling systems, and renewable energy sources. The flexibility of the cloud also allows organisations to dynamically provision resources and optimise their usage, potentially reducing idle capacity and associated emissions.

Focusing specifically on energy efficiency, Cloud providers often use custom hardware with a lower power demand. Generally speaking, it is in their interests to use the most energy efficient hardware possible to reduce their own operating costs. This also allows users to switch to lower powered hardware without the initial outlay for new hardware. Improved energy efficiency also extends to the typical Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) of a cloud-based data centre, which can be lower than typical on-premise data centres.

| Provider | PUE |

|---|---|

| Alibaba Cloud | 1.3 |

| AWS | 1.135 |

| Azure | 1.185 |

| GCP | 1.1 |

| Oracle Cloud | 1.15 * |

| Worldwide Data centre Average | 1.58 - 1.8 |

* Oracle figure is not an average, sourced from information describing their lowest PUE. Sources: 1 2

While Cloud PUE figures may be lower than many on-premise data centres, these figures should be considered carefully when sourced from the Cloud Providers themselves. For example, they may apply to specific data centres only, rather than being an average. In future it is hoped that these figures can be further reduced by recapturing the waste heat from data centres, with Deep Green being an example of a smaller Cloud provider whose micro data centres extract heat to provide hot water for a range of purposes, which can give PUE figures as low as 1.001.

The region that the services are run from likely has an even more significant impact on carbon emissions, depending on the mix of renewable energy sources that power the underlying data centres. One advantage of using cloud is that is easier to move infrastructure to a new location with a better energy mix than it would be when hosting those servers on-premise. Regardless of the grid mix of the location, some cloud providers may report that they use ‘zero carbon’ energy but it is important to distinguish between direct renewable power to the data centre and that which has been offset via Power Purchase Agreements or Renewable Energy Certificates.

The types of services used can also have an impact on emissions, with Infrastructure as a Service offerings potentially providing negligible benefits over already virtualised on-premise hardware. These services may allow the most control over cloud resources but they retain the same issues that can be seen when running on-premise, with instances being allocated to cope with peak load going underutilised for the majority of time.

Platform as a Service options may provide more opportunities for the Cloud provider to choose more efficient usage patterns behind the scenes. This extends to so called ‘Serverless’ options, which provide ways of allocating resources that only exist when work is happening, minimising the impact of idle hardware. Unfortunately the term has become slightly overloaded, with some services still requiring a minimum sized instance to run at all times, so careful reading of documentation may be necessary to determine if services can truly scale to zero.

Cloud services rely on virtualisation to share their server hardware between multiple tenants, allowing for a higher average utilisation than most on-premise data centres. This can be in the range of ~50% utilisation compared to ~20% in a traditional data centre.3 Cloud providers also offer ‘Spot Instances’ as a way of making use of hardware that would otherwise be underutilised.

It is worth noting that making best use of these features may require investment to refactor existing code. A ‘lift and shift’ approach may be the quickest way to transition to using Cloud services, but it should ideally be the first step in an ongoing process to re-architect your software to deliver reductions in emissions.

Quantifying the Emissions of Cloud Services

Cloud providers may provide data on the emissions that are attributable to service use, but what is included may vary and there can be a significant time delay to these figures. Here is a breakdown of the top 3 providers’ own tools.

| Provider | GHG Scopes Covered | Interface | Latency | Granularity | Location vs market based accounting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWS | 1,2 | Dashboard | Monthly (with 3 month delay) |

Coarse - EC2 and S3 are listed individually, all other services grouped as one figure. Location breakdown by continent, not per region Rounds down figures to the nearest 0.1 tCO2e |

Market-based |

| Azure | 1,2,3 | Power BI | Monthly | Fine grained | Market-based |

| GCP | 1,2,3 | Dashboard | Monthly | Fine grained | Location-based |

Due to the delays and inconsistencies, third-party alternatives like Cloud Carbon Footprint have arisen, which provide estimates based on the usage data available from each provider. While tools like these cannot include Scope 1 emissions data, having much closer to real time data can be useful in attempting to optimise cloud service usage for carbon emissions. For more detailed analysis, see Tools for measuring Cloud Carbon Emissions, which covers the available tools for measuring the carbon emissions of cloud services.

There are many sources of information on how to use the cloud in a sustainable manner, with each of the main 3 providers having their own best practices pages (AWS, Azure, GCP). For a more independent view, look to the Green Software Foundation’s Green Software Patterns, which have a specific subsection for Cloud.